Mengino:Far away from any road, deep in the

highlands, lies the village of Mengino. It's a place where I

was the first tourist to visit. It's not a place one can

easily forget.

I headed off to the Goroka airport to meet the bush pilot,

Robert. When asked if we were going to fly the twin engine

plane on the tarmac, he replied, “That? We’re landing on the

steepest runway in New Guinea, a 15% grade. We could land in

that but never take off. We’re taking that (single-engine)

plane over there.” The flight was beautiful with endless

sharp ridges covered in green and periodically, a hut would appear in

the middle of nowhere but then it was back to continuous

forest. Robert pointed to a tiny gash in the jungle cover

under the tall walls of an amphitheater of rock. It was hard

to believe that was a landing strip, but it was and he did an excellent

job of bringing us gently down.

We had landed in Maimafu, one of the villages on the trek around Crater

Mountain. There was a French group making a film about tree

kangaroos. They were nice folks and being French, naturally

had good food with them and freely shared it. When told that

I often ate dried spaghetti on the trails, they were amazed. Well,

actually the word “shocked” might be a better description.

They were trying to get out into the bush to film but were having last

minute problems with the village chief trying to wrangle extra money

out of the deal.

The

next morning I

woke up to the sun just coming over the mountain.

The air was perfectly still with mist rising off the trees and grasses.

What a perfect start to a day. I talked to a guide about

going around the mountain and he brings me to see the chief.

He immediately starts throwing around large numbers and a single fee

becomes two and three fees. A 14 Kina activity (1 Kina = .4

US$) becomes 70 Kina and it just kept going on and on. The

idea of Crater Mountain was that everything is a fixed price so you

don’t have these hassles. He offered me some food, but

declined not knowing if any strings were attached. It went on

like this the next day and a half. When I took a walk to a

waterfall, the people were great but as soon as the chief got involved,

it became very unpleasant. I couldn’t walk around the

mountain and had to stay put seeing that:

The

next morning I

woke up to the sun just coming over the mountain.

The air was perfectly still with mist rising off the trees and grasses.

What a perfect start to a day. I talked to a guide about

going around the mountain and he brings me to see the chief.

He immediately starts throwing around large numbers and a single fee

becomes two and three fees. A 14 Kina activity (1 Kina = .4

US$) becomes 70 Kina and it just kept going on and on. The

idea of Crater Mountain was that everything is a fixed price so you

don’t have these hassles. He offered me some food, but

declined not knowing if any strings were attached. It went on

like this the next day and a half. When I took a walk to a

waterfall, the people were great but as soon as the chief got involved,

it became very unpleasant. I couldn’t walk around the

mountain and had to stay put seeing that:

1) The next village will beat up the

Maimafu guides as they don’t get along

2)It’s Sabbath day

3)Their feet hurt (one look at their

feet of iron and you’ll know this is bull)

I finally convinced them to bring me to Mengino, the closest village

five hours away but the chief will only “allow” me to go there for one

day. I’m extremely uncomfortable being stuck somewhere

without having the power to do anything about it. I tell the

chief, “I’m going to Mengino tomorrow and returning when I feel like

it. You can make guiding fees or I will say in a local’s hut

until the plane returns and you will make nothing. It’s up to

you.”

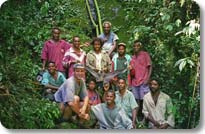

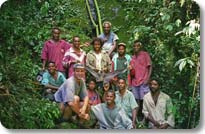

The next day a guide brought me to Mengino, a village of 100-150

people. We walked about five hours through the jungle along a

track worn smooth by age old footsteps. I arrived in the

village and some kids flocked towards me and others ran away. This

white man was immediately the center of attention of the entire

village. I went for water and a dozen kids watched in rapt

attention, completely dedicated to watching the task.

Returning to my hut to lie down, there were people watching me through

the doorway and kids peering at me from cracks between the

boards. The hut was a traditional building made

from all bush materials using a machete, tied together with vines,

topped off by a thatched roof. I lay down in the smoky hut

and looked around and thought, “Good heavens, this is a long way from

home.”

Nimson, the chief, stopped by. He said, “You’re the first

tourist to ever visit our village. Did you notice that some

of the kids ran away from you? That’s because they’ve never

seen a white person before.” I replied, “At home the kids

also run away from me, but that’s because their mothers warn them about

me.” He laughed and when asked if I really was the first one,

he said I was. He brought me to the center of the village and

everyone gathered around.

They

would ask me

questions like, “tell us about New York,” or “What is

Australia like?” They would listen to my every word, every

eye focused on me. Only a few could speak English but there

was one guy who reacted to everything I said. Every funny

word or gesture made him laugh and he was wide-eyed at every

story. But for the most part, Nimson was

translating. A skyscraper was initially described as, “The

cities have buildings made of stone and steel that are 400 meters

tall.” When Nimson translated, he went on and on and pointed

to the mountains nearby. Then I realized that for someone who

lived in houses made entirely from bush materials, he had to put it in

terms they could understand. How do you explain a subway to

someone who has never seen a train? Yet based on their

reactions, somehow Nimson managed to get it across to them.

The nearest road to Mengino is 90 difficult km. away and I was told

that for people deep in the bush, they’ve seen more airplanes than cars.

They

would ask me

questions like, “tell us about New York,” or “What is

Australia like?” They would listen to my every word, every

eye focused on me. Only a few could speak English but there

was one guy who reacted to everything I said. Every funny

word or gesture made him laugh and he was wide-eyed at every

story. But for the most part, Nimson was

translating. A skyscraper was initially described as, “The

cities have buildings made of stone and steel that are 400 meters

tall.” When Nimson translated, he went on and on and pointed

to the mountains nearby. Then I realized that for someone who

lived in houses made entirely from bush materials, he had to put it in

terms they could understand. How do you explain a subway to

someone who has never seen a train? Yet based on their

reactions, somehow Nimson managed to get it across to them.

The nearest road to Mengino is 90 difficult km. away and I was told

that for people deep in the bush, they’ve seen more airplanes than cars.

They would ask me about my family, whether I had a garden (something

every single one of them had), if I was married, and about religious

beliefs (now this is a tricky question you want to be careful

about). One asked, “We heard gossip that man came from

monkeys, is this true?” That’s another tricky one. Others

heard that we were very rich in the U.S., which I didn’t deny but when

I told them a month’s apartment rent in a mid-sized city is about

two-years of their income, they gasped. Another popular

question was about the animals. They really like the

description of moose and skunks. They would also tell me of

their lives and how far they travel to the nearby villages and their

farms. When I told them of frozen lakes, winter

snows, and that in the fall our trees turn pink, orange, yellow, and

red, they stared in disbelief.

After a few hours, Nimson brought me to a hut and we sat around the

fire and talked. He has been all around PNG as a health worker and was

a lot more knowledgeable of the outside world than most people in the

area but he said, “I knew that I had to come back to Mengino.

I’m a person from the bush and this is my home.” We stayed up

late talking around the fire. One group sat in the corner

playing cards and the rest of the guys were along the walls sleeping,

piled all over each other like a stack of firewood, but Nimson and I

both got places next to the fire and had a lot of room to spare, yep,

it’s good to be the chief. It turns out the guys were all

sleeping in the hut as it was the men’s hut. They had a rugby

game coming up with a neighboring village and they couldn’t be near

women before the big game. I was awakened in the middle of

the night by something rubbing against me. I had no idea what

it was, but didn’t like the way it felt. It felt like it was

part of a rhinoceros but then I realized it was a guy’s foot as he was

turning over in his sleep. These folks have never worn shoes

and the only way to describe their feet is like a rhino’s (not that

I’ve ever felt a rhino foot). Over in the corner there was

still a group playing cards in the middle of the night. Early

in the morning, someone got up to stoke the fire and threw some taro

(similar to a potato) into the hot ashes. Breakfast would be

ready in a few hours.

Once

again in the

morning, I found myself surrounded by thirty

whispering people. They followed me around the village, but

it’s ok, I didn’t mind. They followed me to the bathroom,

though at this time they were waved them off. Tolerance ends

at the outhouse. I had another question and answer session

and was asked about the frequent earthquakes they felt and inquired

more about my family. They told me about bride

price. This is a tradition where a man gives gifts and money

to the bride’s family. Typically it consists of 2000-3000

kina, farm tools, traditional gifts of bows and arrows, birds of

paradise feathers, billums (woven bag for carrying goods), and stone

axes. But it also includes pigs, a minimum of five and

sometimes more. You have to provide the pigs lest you insult

the other family. Pigs are status symbols and one needs to be

liberal with the cloven-hoofed goods. I told them in the

U.S., people usually exchange rings. They seemed to think

pigs were a much better idea (and tastier).

Once

again in the

morning, I found myself surrounded by thirty

whispering people. They followed me around the village, but

it’s ok, I didn’t mind. They followed me to the bathroom,

though at this time they were waved them off. Tolerance ends

at the outhouse. I had another question and answer session

and was asked about the frequent earthquakes they felt and inquired

more about my family. They told me about bride

price. This is a tradition where a man gives gifts and money

to the bride’s family. Typically it consists of 2000-3000

kina, farm tools, traditional gifts of bows and arrows, birds of

paradise feathers, billums (woven bag for carrying goods), and stone

axes. But it also includes pigs, a minimum of five and

sometimes more. You have to provide the pigs lest you insult

the other family. Pigs are status symbols and one needs to be

liberal with the cloven-hoofed goods. I told them in the

U.S., people usually exchange rings. They seemed to think

pigs were a much better idea (and tastier).

The men sang a courtship song for me (err…I hope that they were giving

me a cultural demonstration and not actually courting me if you know

what I mean) and they told me about their dating rituals. You

ask a girl’s father if you can date her. If so, you will date

for a month or so and then determine if you want to marry. If

you do, then you raise bride price, usually with family members helping

out and you get married. It’s all pretty cut and

dried. I described dating in the U.S. and how my sister was

seeing a guy for years. First it was on and then off, then

they needed time apart and then they were inseparable, and then they

were…four years later it was finally and firmly determined that…no

wait..she wasn’t so sure anymore. One of the villagers

commented, “She sounds indecisive.” “Bingo! You’ve

got it!” I replied. They all agreed that they prefer their

system of dating. One guy asked if he could marry my

sister. I told him I’d get back to him on that.

The basis of Mengino and in fact the entire backcountry of the region

is agriculture, most of which is subsistence based. Every

single family has land with a farm and pretty much every day they

dedicate part of it to taking care of their crops. There is

some trade in crops with the “outside” world. While this is

limited, it is their primary source of cash income. For

example, Robert spends a lot of time ferrying coffee from the highlands

interior to the coffee exchange in Goroka. There is a system

set up to keep track of how much they sell and how they get

paid. When a person needs to buy a shovel for their garden,

it’s paid for primarily by this trade. There were some

efforts to move the villages into raising vanilla when I was

there. Coffee is a fairly bulky crop, while vanilla is one

that is significantly smaller and less money would be spent on

transporting it but at that time coffee was king (and queen).

They brought me into the gardens to show me how they raised their food.

Several people had tarps in the center of the village covered in coffee

beans drying in the sun. Other crops that are very common are

taro and kaukau (sweet potato). Both of these are very common

in the highlands diet and spend anytime there and you’ll be sure to

have plenty.

Nimson and I talked

a lot about village life and his role in

it. There had never been a government official in Mengino and

if one came, he would tell them to go away and leave them

alone. They are absolutely, completely indifferent to what

happens in the capital, Port Moresby. The only interaction

they have with the government is they pay some tax on the coffee they

sell. He mentioned that he maintained the village “court

system.” If there was a fight in the village,

Nimson would talk to the people involved and make a decision as to how

to deal with it and it would all be taken care of quite

quickly. There was one fight when I was there that everyone

went running to see, but I felt it best to hold back and keep a

distance. I explained our judicial system of the preliminary

hearings, the pleading of innocence or guilt, the jury trial, the

lawyers, the months of time and expense, the appeals court and the

like. The people shook their heads. Like dating,

they preferred their system of justice.

Nimson and I talked

a lot about village life and his role in

it. There had never been a government official in Mengino and

if one came, he would tell them to go away and leave them

alone. They are absolutely, completely indifferent to what

happens in the capital, Port Moresby. The only interaction

they have with the government is they pay some tax on the coffee they

sell. He mentioned that he maintained the village “court

system.” If there was a fight in the village,

Nimson would talk to the people involved and make a decision as to how

to deal with it and it would all be taken care of quite

quickly. There was one fight when I was there that everyone

went running to see, but I felt it best to hold back and keep a

distance. I explained our judicial system of the preliminary

hearings, the pleading of innocence or guilt, the jury trial, the

lawyers, the months of time and expense, the appeals court and the

like. The people shook their heads. Like dating,

they preferred their system of justice.

Nimson and I spent a long time talking in the afternoon. I

told him of the guy who so enjoyed our conversations and how he laughed

so much. An hour later, the Laughing Man sat down outside the

hut. I said, “That’s the one who laughed so hard.”

He responded, “Him?

That’s my brother, he’s deaf and

dumb!” I can be pretty animated when talking so he must have

been responding to my gestures but either way, it appears that we both

got a lot out of our encounters and that’s good. Maybe there

is some sort of universal language. Nimson discussed some of

the needs of the village, specifically medical needs. He has

medical training and can utilize whatever supplies I could help them

with. He did write down some things he could use and I agreed

to help them. I’m all for trying to help the village as long

as it’s not supplying “gifts” which would only be used by a single

person. During our talks, for some reason I mentioned

McDonalds. Not one single person had any idea what that

was. You know, I’m really liking these people.

Later we went out to watch the “mob”, as Nimson called them, play

rugby. They played on hard ground, which made thudding noises

as bodies hit the earth. They would get up and keep

running. These guys were tough and there is no way you could

have gotten me out there to play as the phrase “scraped off the ground”

would have been appropriate. I look around at the people from

home and see them winded after a flight of stairs whereas these people

are out every day working hard. An eight hour walk to the

next village? No problem, even the older people will do it

all the time. Nimson wandered off and an older woman

approached me and started speaking the local language. She

pulled up her shirt and grabbed her breasts and started pointing them

around at the people gathered round. It was a decidedly

uncomfortable situation. I had no idea what she was saying or

how to react. Do you ignore her or do you respect the elders,

although my urge was to run away screaming. Nobody seemed

alarmed at what was happening, except for me of course, although some

were giggling at my apparent discomfort. She kept going on

and pointing her breasts around, “Help…help” I murmured but the English

speakers were nowhere to be seen. Finally someone came by when he

noticed my discomfort. He said, “She was asking how you could

be away from your family for so long. She was pointing to her

children and saying that she breastfed them all and has never been more

than a day’s walk away from them.” She was pointing her

breasts at her grown children?! We need to accept that others have

different ways, but Mom, if you’re reading this…never do that…ever.

At night, we gathered around the hut fire, talked into the late hours

and had a dinner of taro. One of the older men told me what

it was like when they first saw white people. You know,

that’s the sort of thing you read about but here it was, front and

center. We talked about a wide variety of subjects and I even

gave a brief description of the internet. They are quite

curious about things that are far beyond their horizons but have

limited ability to learn of those things due to their

remoteness. Nimson sees very little change for Mengino in the

years ahead. It’s too isolated and poor. They’re

working on getting people to read, not program computers.

Earlier that day I saw an adult learning to read from a children’s

book, one of the very few books I saw. Nimson said, “We have

people who can teach reading, what we lack is books.”

There really are very few options for them there and I fear that over

time, the isolated villages might start to depopulate as they have in

so many places around the world. There is a certain

timelessness to them but they have to make their own choices and it’s

not up to me what they choose. Nimson did ask about satellite

TV and what it would cost. I went through the expenses of a

dish, monthly subscription, generator and fuel, which is out of their

reach right now. In the corner, people were still playing

cards. One replied, “They can go on for days.”

In the morning, I thought about the TV discussion with Nimson last

night. It’s not up to me to decide what they are going to do

but I thought it best to balance the information they

received. I said, “If you get TV, you need to consider how it

will change your village. Yes, it can bring great

information, but it would mostly be garbage. You have a very

rich social life here with people gathering around the fire and talking

to each other while looking at each other. If you get a TV,

the attention will all be focused on the TV and not each

other. It will affect things socially.” I

emphasized how I wasn’t telling him what to do, but there are changes

that would happen. Nimson said, “I’ll have to think about

it. I never considered these things.”

In the

afternoon the

mob decided to bring me into the bush.

They said, “We’ll get our bows and arrows.” I was really

surprised, yep, they got them. I’m a pretty strong hiker but

compared to these guys, I’m a sissy…a big sissy.

Earlier I

told them how men didn’t hold hands in our culture and if a man held my

hand, I would be uncomfortable. We were climbing a hill and I was

slipping on the logs. The mob, in their bare feet, were

racing up. Someone said, “Grab his hand and help him

up.” Nimson said, “NO! It’s against his

culture.” That made me laugh, “Nimson, you can grab my hand

to help me up as long as you let go at the top.” My friend

liked that. The mob’s machetes were flying as they cleared a

path in the fast growing jungle. I have to say, these guy

were strong and could keep doing this all day long.

In the

afternoon the

mob decided to bring me into the bush.

They said, “We’ll get our bows and arrows.” I was really

surprised, yep, they got them. I’m a pretty strong hiker but

compared to these guys, I’m a sissy…a big sissy.

Earlier I

told them how men didn’t hold hands in our culture and if a man held my

hand, I would be uncomfortable. We were climbing a hill and I was

slipping on the logs. The mob, in their bare feet, were

racing up. Someone said, “Grab his hand and help him

up.” Nimson said, “NO! It’s against his

culture.” That made me laugh, “Nimson, you can grab my hand

to help me up as long as you let go at the top.” My friend

liked that. The mob’s machetes were flying as they cleared a

path in the fast growing jungle. I have to say, these guy

were strong and could keep doing this all day long.

They brought me to their birthing cave. When a

woman is about

to give birth, she comes here with a mid-wife. Everyone in the mob had

been born there. In the cave, they showed me how they made

fire with a stick and bark. They split a stick about the

thickness of a finger and put a smaller stick in the split to hold it

open. They cut off a thin piece of bark and quickly rubbed it

back and forth across the split, holding it above dried

leaves. In fifteen seconds, they were blowing on the

smoldering leaves. I was impressed at how quickly they could

do it. I told them how I could make fire with flint and steel

but it wasn’t completely from bush materials. On the walk

home, the mob spotted something to hunt in the distance. They

took chase and zoom! They were gone. Good

heavens are they fast.

That evening we, once again, as is usual in the village, sat around the

fire and talked. Many people were interested in my thoughts

about the end of time, among other subjects. This is a keen

interest of theirs and they tried to relate some of what I told them

was going on in the rest of the world with their beliefs in this

subject. However we were distracted from such deeper subjects

with the arrival of dinner, which consisted of taro (naturally) and a

special treat of corn on the cob. You have to like

that. Nimson asked if he would be able to write me while I

was traveling. I told him that he could send a letter to my

mom, who would take a picture of it and then he interjected, “She’ll

send it to you on the internet?” I think he was starting to

understand.

On my last day, we

went to the base of a cliff above Mengino, at the

top of which was cave with bats inside. On the way there,

they found a big, grasshopper-like bug and showed it to me.

They didn’t catch it for showing off, but for food. Nimson

said that he didn’t want to return without bringing something for his

daughter. He killed it and wrapped it in a leaf to bring

home. I have to say, I’m certainly glad they didn’t give it

to me as I don’t think I would have been able to eat it.

Chocolate covered ants, maybe. Big, juicy, crunchy bugs…I

don’t think so. They continued to pick up various bits of

bush food here and there. They do know the land well, that’s

for sure.

On my last day, we

went to the base of a cliff above Mengino, at the

top of which was cave with bats inside. On the way there,

they found a big, grasshopper-like bug and showed it to me.

They didn’t catch it for showing off, but for food. Nimson

said that he didn’t want to return without bringing something for his

daughter. He killed it and wrapped it in a leaf to bring

home. I have to say, I’m certainly glad they didn’t give it

to me as I don’t think I would have been able to eat it.

Chocolate covered ants, maybe. Big, juicy, crunchy bugs…I

don’t think so. They continued to pick up various bits of

bush food here and there. They do know the land well, that’s

for sure.

Once we reached the cliff, they built a ladder twelve meters

tall out

of trees and vines, building it right there on the spot using their

machetes. Some of the mob climbed up with their bows and went

into the cave. Nimson said that he wasn’t going to go up

there because he’s the chief and doesn’t have to and he said I couldn’t

either as I’m the guest (and I suspect he was too worried about me

getting hurt). It’s hard to see as the cave is very dark, but

they managed to get a flying fox, one of the biggest bats in the

world. Nimson told me a traditional tale of bats and I

related our stories of vampires. When told of how

bats echolocate (see in the dark with sound), they were

impressed.

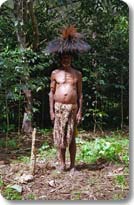

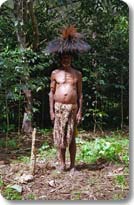

Upon our return one

of the elders dressed up in traditional dress for

me and the children played flutes; yep, they had to show off a little

bit for me, which was nice. Unfortunately this was the last

day in Mengino. The plane was coming tomorrow and I prepared

to leave. I really wished I had allotted more days in the

area. I said goodbye to all and especially to

Nimson. I hoped that one day we would be able to meet

again. Two of Nimson's sons guided me back to

Maimafu. It started to rain and I put on my expensive

synthetic rain jacket. Nimsom’s sons hacked off two-meter

long banana leaves and used them like umbrellas. They sure

did work, were much cheaper, and renewable. Two worlds…two

approaches.

My night in Maimafu was unremarkable and the next day Robert came to

pick me up and made another perfect landing. He said to me,

“We can fly back to Goroka right now or we can fly around for the

afternoon.” “Let’s fly!” I said. So Robert brought

me around to several very isolated villages, dropping goods off and

picking up coffee and other things. One popular item that I

saw on all flights and everywhere in PNG was chicken-flavored Maggi

two-minute noodles. Sad, but true. I tell you, he

brought me places that I never, in a thousand years, thought I would be

able to see.

My night in Maimafu was unremarkable and the next day Robert came to

pick me up and made another perfect landing. He said to me,

“We can fly back to Goroka right now or we can fly around for the

afternoon.” “Let’s fly!” I said. So Robert brought

me around to several very isolated villages, dropping goods off and

picking up coffee and other things. One popular item that I

saw on all flights and everywhere in PNG was chicken-flavored Maggi

two-minute noodles. Sad, but true. I tell you, he

brought me places that I never, in a thousand years, thought I would be

able to see.

Upon return to Goroka, I stayed at a guesthouse and met Burkhardt from

Germany. He liked the sound of Mengino and he ended up

going. Mengino never had an outsider and then they have two

of them. When Burkhardt returned he raved about Mengino and

thanked me for telling him about it. He said, “Everywhere in

Mengino, I could hear people talking in their language, but I would

frequently hear your name among the words. You’re impact is

strongly felt and they won’t forget you.” I replied, “I won’t

forget them either.”

Epilogue:

In

Goroka, I tried

to buy medical supplies for the village that Robert

said he would deliver for me, but the banks were closed for several

days. I was able to buy a rugby ball for them.

In

Goroka, I tried

to buy medical supplies for the village that Robert

said he would deliver for me, but the banks were closed for several

days. I was able to buy a rugby ball for them.

A few years later, I made a donation through the Research and

Conservation Foundation which helps villages in the area.

Everyone I talked to agreed they were very good to deal with.

I donated around $300 for medical supplies and coordinated it with the

RCF. We were both very clear about what the donation would be

used for and they would ensure compliance. They wouldn’t give

the money to Mengino; rather they would ask what sort of supplies they

need and would buy them for the people to avoid corruption

issues. A year later, I wanted to make another donation and

the RCF asked me what sort of arrangement I made with Nimson as somehow

Nimson had somehow converted my donations to personal use.

Nimson told the RCF that it was repayment for taking care of me in

Mengino.

I really want to help the people of Mengino but if Nimson is going to

misuse the money, what can I do? It saddens me, but my will

to help seems to have grown distant.

The

next morning I

woke up to the sun just coming over the mountain.

The air was perfectly still with mist rising off the trees and grasses.

What a perfect start to a day. I talked to a guide about

going around the mountain and he brings me to see the chief.

He immediately starts throwing around large numbers and a single fee

becomes two and three fees. A 14 Kina activity (1 Kina = .4

US$) becomes 70 Kina and it just kept going on and on. The

idea of Crater Mountain was that everything is a fixed price so you

don’t have these hassles. He offered me some food, but

declined not knowing if any strings were attached. It went on

like this the next day and a half. When I took a walk to a

waterfall, the people were great but as soon as the chief got involved,

it became very unpleasant. I couldn’t walk around the

mountain and had to stay put seeing that:

The

next morning I

woke up to the sun just coming over the mountain.

The air was perfectly still with mist rising off the trees and grasses.

What a perfect start to a day. I talked to a guide about

going around the mountain and he brings me to see the chief.

He immediately starts throwing around large numbers and a single fee

becomes two and three fees. A 14 Kina activity (1 Kina = .4

US$) becomes 70 Kina and it just kept going on and on. The

idea of Crater Mountain was that everything is a fixed price so you

don’t have these hassles. He offered me some food, but

declined not knowing if any strings were attached. It went on

like this the next day and a half. When I took a walk to a

waterfall, the people were great but as soon as the chief got involved,

it became very unpleasant. I couldn’t walk around the

mountain and had to stay put seeing that: They

would ask me

questions like, “tell us about New York,” or “What is

Australia like?” They would listen to my every word, every

eye focused on me. Only a few could speak English but there

was one guy who reacted to everything I said. Every funny

word or gesture made him laugh and he was wide-eyed at every

story. But for the most part, Nimson was

translating. A skyscraper was initially described as, “The

cities have buildings made of stone and steel that are 400 meters

tall.” When Nimson translated, he went on and on and pointed

to the mountains nearby. Then I realized that for someone who

lived in houses made entirely from bush materials, he had to put it in

terms they could understand. How do you explain a subway to

someone who has never seen a train? Yet based on their

reactions, somehow Nimson managed to get it across to them.

The nearest road to Mengino is 90 difficult km. away and I was told

that for people deep in the bush, they’ve seen more airplanes than cars.

They

would ask me

questions like, “tell us about New York,” or “What is

Australia like?” They would listen to my every word, every

eye focused on me. Only a few could speak English but there

was one guy who reacted to everything I said. Every funny

word or gesture made him laugh and he was wide-eyed at every

story. But for the most part, Nimson was

translating. A skyscraper was initially described as, “The

cities have buildings made of stone and steel that are 400 meters

tall.” When Nimson translated, he went on and on and pointed

to the mountains nearby. Then I realized that for someone who

lived in houses made entirely from bush materials, he had to put it in

terms they could understand. How do you explain a subway to

someone who has never seen a train? Yet based on their

reactions, somehow Nimson managed to get it across to them.

The nearest road to Mengino is 90 difficult km. away and I was told

that for people deep in the bush, they’ve seen more airplanes than cars. Once

again in the

morning, I found myself surrounded by thirty

whispering people. They followed me around the village, but

it’s ok, I didn’t mind. They followed me to the bathroom,

though at this time they were waved them off. Tolerance ends

at the outhouse. I had another question and answer session

and was asked about the frequent earthquakes they felt and inquired

more about my family. They told me about bride

price. This is a tradition where a man gives gifts and money

to the bride’s family. Typically it consists of 2000-3000

kina, farm tools, traditional gifts of bows and arrows, birds of

paradise feathers, billums (woven bag for carrying goods), and stone

axes. But it also includes pigs, a minimum of five and

sometimes more. You have to provide the pigs lest you insult

the other family. Pigs are status symbols and one needs to be

liberal with the cloven-hoofed goods. I told them in the

U.S., people usually exchange rings. They seemed to think

pigs were a much better idea (and tastier).

Once

again in the

morning, I found myself surrounded by thirty

whispering people. They followed me around the village, but

it’s ok, I didn’t mind. They followed me to the bathroom,

though at this time they were waved them off. Tolerance ends

at the outhouse. I had another question and answer session

and was asked about the frequent earthquakes they felt and inquired

more about my family. They told me about bride

price. This is a tradition where a man gives gifts and money

to the bride’s family. Typically it consists of 2000-3000

kina, farm tools, traditional gifts of bows and arrows, birds of

paradise feathers, billums (woven bag for carrying goods), and stone

axes. But it also includes pigs, a minimum of five and

sometimes more. You have to provide the pigs lest you insult

the other family. Pigs are status symbols and one needs to be

liberal with the cloven-hoofed goods. I told them in the

U.S., people usually exchange rings. They seemed to think

pigs were a much better idea (and tastier). Nimson and I talked

a lot about village life and his role in

it. There had never been a government official in Mengino and

if one came, he would tell them to go away and leave them

alone. They are absolutely, completely indifferent to what

happens in the capital, Port Moresby. The only interaction

they have with the government is they pay some tax on the coffee they

sell. He mentioned that he maintained the village “court

system.” If there was a fight in the village,

Nimson would talk to the people involved and make a decision as to how

to deal with it and it would all be taken care of quite

quickly. There was one fight when I was there that everyone

went running to see, but I felt it best to hold back and keep a

distance. I explained our judicial system of the preliminary

hearings, the pleading of innocence or guilt, the jury trial, the

lawyers, the months of time and expense, the appeals court and the

like. The people shook their heads. Like dating,

they preferred their system of justice.

Nimson and I talked

a lot about village life and his role in

it. There had never been a government official in Mengino and

if one came, he would tell them to go away and leave them

alone. They are absolutely, completely indifferent to what

happens in the capital, Port Moresby. The only interaction

they have with the government is they pay some tax on the coffee they

sell. He mentioned that he maintained the village “court

system.” If there was a fight in the village,

Nimson would talk to the people involved and make a decision as to how

to deal with it and it would all be taken care of quite

quickly. There was one fight when I was there that everyone

went running to see, but I felt it best to hold back and keep a

distance. I explained our judicial system of the preliminary

hearings, the pleading of innocence or guilt, the jury trial, the

lawyers, the months of time and expense, the appeals court and the

like. The people shook their heads. Like dating,

they preferred their system of justice.  In the

afternoon the

mob decided to bring me into the bush.

They said, “We’ll get our bows and arrows.” I was really

surprised, yep, they got them. I’m a pretty strong hiker but

compared to these guys, I’m a sissy…a big sissy.

Earlier I

told them how men didn’t hold hands in our culture and if a man held my

hand, I would be uncomfortable. We were climbing a hill and I was

slipping on the logs. The mob, in their bare feet, were

racing up. Someone said, “Grab his hand and help him

up.” Nimson said, “NO! It’s against his

culture.” That made me laugh, “Nimson, you can grab my hand

to help me up as long as you let go at the top.” My friend

liked that. The mob’s machetes were flying as they cleared a

path in the fast growing jungle. I have to say, these guy

were strong and could keep doing this all day long.

In the

afternoon the

mob decided to bring me into the bush.

They said, “We’ll get our bows and arrows.” I was really

surprised, yep, they got them. I’m a pretty strong hiker but

compared to these guys, I’m a sissy…a big sissy.

Earlier I

told them how men didn’t hold hands in our culture and if a man held my

hand, I would be uncomfortable. We were climbing a hill and I was

slipping on the logs. The mob, in their bare feet, were

racing up. Someone said, “Grab his hand and help him

up.” Nimson said, “NO! It’s against his

culture.” That made me laugh, “Nimson, you can grab my hand

to help me up as long as you let go at the top.” My friend

liked that. The mob’s machetes were flying as they cleared a

path in the fast growing jungle. I have to say, these guy

were strong and could keep doing this all day long.

On my last day, we

went to the base of a cliff above Mengino, at the

top of which was cave with bats inside. On the way there,

they found a big, grasshopper-like bug and showed it to me.

They didn’t catch it for showing off, but for food. Nimson

said that he didn’t want to return without bringing something for his

daughter. He killed it and wrapped it in a leaf to bring

home. I have to say, I’m certainly glad they didn’t give it

to me as I don’t think I would have been able to eat it.

Chocolate covered ants, maybe. Big, juicy, crunchy bugs…I

don’t think so. They continued to pick up various bits of

bush food here and there. They do know the land well, that’s

for sure.

On my last day, we

went to the base of a cliff above Mengino, at the

top of which was cave with bats inside. On the way there,

they found a big, grasshopper-like bug and showed it to me.

They didn’t catch it for showing off, but for food. Nimson

said that he didn’t want to return without bringing something for his

daughter. He killed it and wrapped it in a leaf to bring

home. I have to say, I’m certainly glad they didn’t give it

to me as I don’t think I would have been able to eat it.

Chocolate covered ants, maybe. Big, juicy, crunchy bugs…I

don’t think so. They continued to pick up various bits of

bush food here and there. They do know the land well, that’s

for sure. My night in Maimafu was unremarkable and the next day Robert came to

pick me up and made another perfect landing. He said to me,

“We can fly back to Goroka right now or we can fly around for the

afternoon.” “Let’s fly!” I said. So Robert brought

me around to several very isolated villages, dropping goods off and

picking up coffee and other things. One popular item that I

saw on all flights and everywhere in PNG was chicken-flavored Maggi

two-minute noodles. Sad, but true. I tell you, he

brought me places that I never, in a thousand years, thought I would be

able to see.

My night in Maimafu was unremarkable and the next day Robert came to

pick me up and made another perfect landing. He said to me,

“We can fly back to Goroka right now or we can fly around for the

afternoon.” “Let’s fly!” I said. So Robert brought

me around to several very isolated villages, dropping goods off and

picking up coffee and other things. One popular item that I

saw on all flights and everywhere in PNG was chicken-flavored Maggi

two-minute noodles. Sad, but true. I tell you, he

brought me places that I never, in a thousand years, thought I would be

able to see. In

Goroka, I tried

to buy medical supplies for the village that Robert

said he would deliver for me, but the banks were closed for several

days. I was able to buy a rugby ball for them.

In

Goroka, I tried

to buy medical supplies for the village that Robert

said he would deliver for me, but the banks were closed for several

days. I was able to buy a rugby ball for them.